Other People’s Ideas

Other People's Ideas

Calvin Staples, MSc, will be selecting some of the more interesting blogs from HearingHealthMatters.org which now has almost a half a million hits each month. This blog is the most well read and best respected in the hearing health care industry and Calvin will make a regular selection of some of the best entries for his column, Other People’s Ideas.

As a clinical audiologist, I am always looking for new ways to connect with my patients and to ensure I meet their needs or expectations. Audiologists have many scales and validation measures to gain insight into hearing aid success or failures, but what about the overall patient experience? The ability to tailor the patient experience to their expectations is helpful in gaining patient trust. In a competitive marketplace, gaining patient trust is one of the few factors directly related to what the clinician provides to the overall experience. I have provided some blogs aimed at providing some touch points on patient experiences.

Best of Hearing Health: Two Ways to Show Patients their Hearing Aids are Helping

Originally posted at HHTM On April 20, 2016. Reprinted with permission.

If you are an audiologist, it is easy to delude yourself into thinking that people will listen to you and accept what you are saying. You spent a lot of time and energy going to graduate school, and you have a license to practice Audiology. So, because you are a trusting individual, you believe other people will listen to you, and trust you. Sadly, this is often not the case.

One of the great weaknesses of any profession, including ours, is that our professional training does not give us a “real world” orientation. Audiology students in a typical graduate school do not learn much about the realities of life and business. All too often, new graduates enter practice without a good understanding of the basic human nature of the patients they will be caring for.

People have their own “judgment systems” that are strongly influenced by their age, culture, and individual differences. If you become adept at relating to a wide range of people and if you learn how to sell and fit hearing aids, you will become successful. If you don’t, you won’t. Like a lot of audiologists, my greatest weakness is not in technology, it is in salesmanship.

Some Tips for the Next Generation

Speaking as a veteran Audiologist, let me offer some fatherly advice to young Audiologists.

Every time you see a patient, use some type of demonstration that starkly contrasts the difference between aided and unaided hearing. From the patient’s perspective, this demonstration needs to be black and white. Your demonstration should leave them saying to themselves, “I hear with these hearing aids. I cannot hear without them.”

EFFECTIVE DEMONSTRATIONS

Here are a couple of ways to make this demonstration successful.

Study the patient’s audiogram. If the speech-reception thresholds (SRTs) are above 40 dB and the thresholds for 1000-6000 Hz are above 50 or 60 dB, patients will have trouble hearing the noise they make when they rub their hands together.

The demonstration goes like this: Fit the aids; adjust the volume to a comfortable level; remove the aids. You should also try the hearing aids on your own ears, or measure their output in a test box to make sure you have substantial amplification. Don’t start the demonstration until you’re sure everything is working correctly.

Then, put a hearing aid on the patient’s ear and tell them to rub their hands together. They should be able to hear this noise easily with their aided ear.

Tell the patient, “Keep rubbing,” and then reach over and remove the hearing aid. If you do this correctly, it will be a dramatic demonstration to the patient that the hearing aid enables them to hear sound that is inaudible to them unaided.

SHOW IMPROVED WORD UNDERSTANDING

Here’s another idea. The Tennessee Tonality Words are “test words,” which are grouped by pitch into five tonal groups: Low-pitch (L), Low-Mid (L-M), Mid (M), Mid-High (MH), and High (H).

I use these words to do another type of black-and-white demonstration that shows patients how well they hear words with the hearing aids and how poorly they understand without them.

I ask patients to repeat the words I say. I speak in a normal voice, but cover my mouth so patients can’t read my lips. I adjust the hearing aid to a comfortable level, then remove it. Standing three feet away from the patient, I start uttering some high-pitched words: “itch, teach, ship, beach…” After saying two or three words, I ask the patient to repeat them. If the patient does so correctly, I increase the distance between us and repeat the test.

At some point the patient will no longer be able to hear and repeat the words. For this example, suppose the patient can no longer repeat what I say from 12 feet away. I turn to the family members and ask them, “Can you hear the words?” They usually say, “Yes, easily.”

I then put the hearing aid back in the patient’s ear and ask them to repeat the same words, which I say standing at the same place where the patient was unable to hear me unaided.

If I have set up this demonstration correctly, the patient will be able to hear all the words with the hearing aid, and none of the words without it. I emphasize the difference by asking the family, “Are the hearing aids working?” At this point, the patient’s family members become a very important part of the demonstration, because they typically become excited and are overjoyed that their husband or father will be able to hear.

Demonstrations like these do more than show patients the benefit of the hearing aids. They also keep us honest. If for any reason the fitting is not working correctly, the demonstration will fail. That tells us that something is not working properly and that we need to put extra effort into fine-tuning the fitting.

Cultural Differences in Hearing Aid Use

Originally posted at HHTM On May 20, 2015. Reprinted with permission.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2015) these are the current facts on deafness and hearing loss around the world:

- 360 million people (328 Million and 32 Million children) worldwide have disabling hearing loss (40 dB or greater for the better ear for adults)(greater than 30 dB in the better ear for children). The majority of people with disabling hearing loss live in low and middle income countries. Approximately one-third of people over 65 years of age are affected by disabling hearing loss.

- Hearing loss may result from genetic causes, complications at birth, certain infectious diseases, chronic ear infections, the use of particular drugs, exposure to excessive noise and ageing.

- Half of all cases of hearing loss are avoidable through primary prevention.

- People with hearing loss can benefit from hearing aids, cochlear implants and other assistive devices; captioning and sign language; and other forms of educational and social support.

- Current production of hearing aids meets less than 10% of global need.

Cultural Issues – “New Research”

Those of us that have traveled to various countries realize that there are many cultural differences that affect how patients, their families, and others react to hearing impairment. These cultures react quite differently in in how and if they seek hearing rehabilitation. While the WHO has suggested that 90% of worldwide population with hearing loss could benefit from hearing aids, only a small proportion of them actually seek professional assistance and use hearing aids to reduce the effects of their hearing impairment. This issue prompted a group of researchers, from a number of countries to investigate cultural differences in how patients seek help for their hearing loss and in the adoption hearing aids (Zhao et al (2015). The research group included members from the UK, Sweden, China, and India that discussed health-care systems, audiology services, and how they are used in their respective countries. They considered various theoretical approaches to the understanding of how culture may affect hearing-related behaviors.

Results from the study indicated that different cultural value systems lead to various perceptions and interpretations of situations related to aging, disability, hearing loss, and hearing aid use. Specifically, negative stereotypes about aging and the perception of aging differ widely from one culture to another.  The countries studied represented a broad spectrum on the individualism to collectivism scale, with the UK and Sweden being highly individual. India and even more so China, demonstrating collectivist attitudes. These factors are thought to moderate perceptions of health, disability, and disease, implying that cultural differences lead to different ways of perceiving and interpreting situations related to hearing loss and hearing aid use.

The countries studied represented a broad spectrum on the individualism to collectivism scale, with the UK and Sweden being highly individual. India and even more so China, demonstrating collectivist attitudes. These factors are thought to moderate perceptions of health, disability, and disease, implying that cultural differences lead to different ways of perceiving and interpreting situations related to hearing loss and hearing aid use.

Zhao et al’s conclusions are similar to that of other researchers in that disabilities, such as hearing impairment, and their perceived causes must be viewed within a cultural context. Various cultures view the causes ofdisabilities and, subsequently, their treatments in various ways. Different disciplines, cultures, and individuals do not agree about what “disabilities” are and how to explain them (Smith, 2014).While western cultures typically believe in a direct, scientific cause-and-effect relationship between a biological problem in a developing baby or an elderly adult, less educated cultures often believe that the causes are fate, bad luck, sins of a parent, the food the mother ate, or evil spirits (Cheng, 1995). These alternative views affect the way a child or an adult with a disability is viewed within the culture and the degree to which a family may be willing to pursue intervention to address the person’s disabilities or special needs, i.e. hearing aids. As Audiologists it is necessary to appreciate these differences as we seek to facilitate aural rehabilitative treatment for these patients, but are there more practical issues?

But is the Worldwide Non-Use of Hearing Aids All Cultural?

According to WHO (2015), current hearing instrument production only meets 10% of the needs of the hearing impaired worldwide. According to Strom (2013), the world market for hearing aids is probably just over 10 million units. His estimates include a fairly even three way split among the United States and Canada (about 31% of the world hearing aid market by units), Europe (38%), and Asia, the Pacific Rim (22%) as well as the “rest of the world” (9%) accounting for another almost 1/3 of the total market. The growth of the world market for amplification is about 3-4% which is slow by anyone’s estimation according to the extreme need that exists in the “rest of the world”. While cultural issues are a major component in the worldwide treatment of hearing impairment, there are also many other practical issues that complicate the uptake of amplification in the treatment of hearing impairment around the world, particularly in third world countries. These other issues relate to costs of the products, availability of professionals for the fitting and follow up, distribution capabilities, battery availability and other general concerns. As the field of audiology develops worldwide within the various cultures and the practical issues are circumvented, the use of amplification will be come greater and the cultural acceptance of hearing impairment will follow as it has in more developed countries.

References

Smith, D. (2014). Differing perspective of Disability. Education.com Retrieved May 20, 2015: http://www.education.com/reference/article/differing-perspectives-disabilities/

Strom, K. (2013). Staff standpoint: Worldwide hearing aid sales. Hearing Review. Retrieved May 20, 2015: http://www.hearingreview.com/2013/05/staff-standpoint-worldwide-hearing-aid-sales/

World Health Organization (2015). Deafness and Hearing Loss. Retrieved May 19, 2015: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs300/en/

Zhao F, et al. Exploring the influence of culture on hearing help-seeking and hearing-aid uptake. International Journal of Audiology 2015 Mar 11:1-9.rieved May 19, 2015: http://www.audiology-worldnews.com/news/1336-the-influence-of-culture-on-hearing-help-seeking-and-hearing-aid-uptake

John Starts His Hearing Journey

Originally posted at HHTM On May 20, 2015. Reprinted with permission.

“Peeling the Onion” is a monthly column by Harvey Abrams, PhD.

“Peeling the Onion” is a monthly column by Harvey Abrams, PhD.

For today’s post, I’d like to combine the subjects of two previous, seemingly unrelated “Peeling the Onion” posts – the Transtheoretical (Stages of Change) Model and MarkeTrak (MT) 9. MT9 Goes to the IOM Meeting

On June 30th I attended the Second Meeting of the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Accessible and Affordable Hearing Health Care for Adults that was held at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in Washington DC. Information about this committee and its responsibilities can be found in a previous post by David Kirkwood in HHTM as well as in a recent Hearing Review blog by Karl Strom.

I was asked to provide a brief presentation to the committee on MT9 from the consumer’s perspective.

The readers of HHTM should be generally familiar with MT9 at this point. David Kirkwood provided an excellent overview of MT9 in an earlier post and Jan Kilm and I prepared an article on MT9 for the Hearing Review. Amyn Amlani and I addressed some specific issues associated with the adoption rate in subsequent HHTM posts.

For the purposes of my presentation to the IOM, however, rather than present the committee with a slide deck filled with data, I thought I would attempt to tell the story of MT9 through the context of one patient’s journey. Let’s call him John.

John Starts His Journey

John is 68 years old and recently retired. He is married with grown children and several grandchildren. He’s in good health, physically and socially active, and financially comfortable.

Like many individuals his age, John is beginning to experience increasing hearing and communication problems. Specifically, he’s having to ask his wife and friends to repeat what they’ve said; he’s having problems understanding his children and, particularly, his grandchildren on the phone; he needs to turn up the TV volume to a level that’s becoming uncomfortable for his wife.

If John is anything like the millions of other Americans with adult-onset hearing loss, he is about to embark on a journey that started even before he became aware of his problem and will end, ideally, when he’s satisfied that his communication problems are resolved. Interestingly, the data from MT9 informs us, in very detailed ways, just how that journey is likely to be navigated by John and millions like him.

Mapping John’s Journey with the Transtheoretical Model

John’s journey can be conceptualized through the Transtheoretical Model of behavior change originally introduced to describe a therapeutic approach to smoking cessation and subsequently applied to the management of other therapeutic interventions to include, most recently, audiologic rehabilitation.[1],[2][3] The transtheoretical model recognizes that behavior change is difficult and that most individuals progress (and sometimes, regress) through a 6-stage cyclical process. You may recall that these stages of change are identified as:

- pre-contemplation

- contemplation

- preparation

- action

- maintenance

- relapse

We know that John didn’t wake up one day and decide to purchase hearing aids. Adult onset hearing loss tends to be invisible, painless, and progresses very slowly; so much so that, early in his journey, during the pre-contemplation stage, John may not have even been aware of his hearing difficulties, though others likely were.

It’s possible that John likely blamed others for his problems. As friends and family increasingly raise the issue of his hearing difficulties, John begins to accept the fact that he has a problem and begins to think about doing something about it. He internalizes the advantages and disadvantages of taking action in what’s known as the contemplation stage.

John’s Journey Isn’t a Walk in the Park

John’s internal cost vs. benefit calculus can be illustrated in another model called the Health Belief Model which I’ve also reviewed in a previous post. Before we take action related to a health-related concern, we internalize our susceptibility to the disorder, how serious it is, what the benefits will be if we take action and the barriers that are preventing us from doing so. We weigh those perceived threats against our expectations of the outcomes and decide whether or not to act. In John’s case, this action might be manifested in scheduling a hearing test.

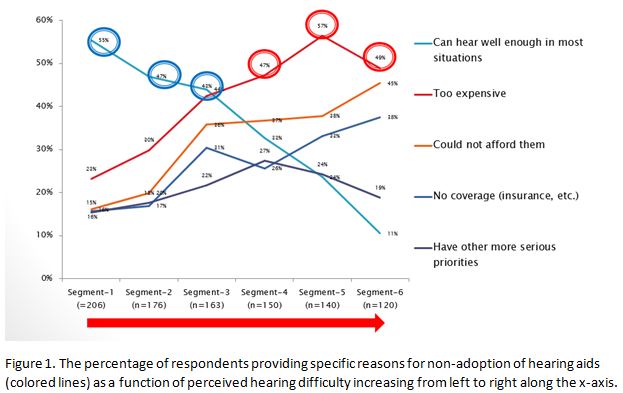

The data from MT9 provides important insight into the perceived barriers to taking action which tend to be a function of the perceived severity of the hearing loss which is consistent with the Health Belief Model. Figure 1 illustrates the reasons respondents in the MT9 survey gave for not taking action. The segments along the bottom of this graph generally represent increasing amounts of perceived hearing difficulty.

Among those with mild to moderate hearing difficulty (segments 1-3), the primary barrier is their perception that they hear well enough in most situations, as represented by the teal line and circles; for those with more severe difficulty (segments 4-6), affordability appears to be the primary barrier as represented by the red line and circles. Expense (orange line) and lack of insurance coverage (blue line) as barriers, also seem to be correlated with the perceived degree of hearing difficulty.

John’s Journey Isn’t a Short Vacation

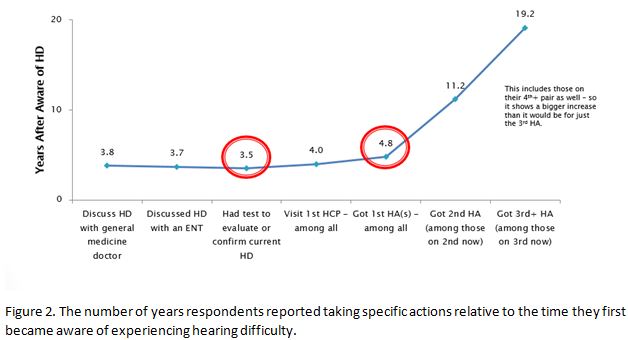

MT9 data suggests that, as a result of these barriers, it will take approximately 3.5 years between the time John was initially aware of his hearing difficulty and when he had his first hearing test and an additional year before he purchases his first hearing aid (Figure 2).

In the next post, I’ll discuss how the MT9 data informs us as to how John prepares to take action as he enters the preparation stage.

This is Part 8 of the Peeling the Onion series. Click here for Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7.

References

- Laplante-Lévesque, A., Hickson, L., & Worrall, L. (2013) Stages of change in adults with acquired hearing impairment seeking help for the first time: application of the transtheoretical model in audiologic rehabilitation. Ear & Hearing, 34(4):447–457 doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3182772c49

- Laplante-Levesque, A. (2015). Applying the stages of change to audiologic rehabilitation. Hearing Review, 68(6), 8-12.

- Manchaiah V, Rönnberg J, Andersson G, Lunner T (2015). Stages of change profiles among adults experiencing hearing difficulties who have not taken any action: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0129107. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129107

Unbundling Service Delivery: Start with the Customer’s Viewpoint

Originally posted at HHTM On May 20, 2015. Reprinted with permission.

If you’ve been keeping up with the professional listservs over the past year or so, you’ve probably heard the chatter about unbundling or itemizing various audiological services. There are many valid economic arguments for unbundling service from the selection and fitting of the device, and it’s ultimately the decision of the owner or manager on how (or if) unbundling gets implemented in a practice.

On the surface unbundling seems fairly straightforward, but once you start digging deeper into actually doing it, things can get a little frantic. The good news is that the Academy of Doctors of Audiology has created a task force that is examining all facets of unbundling and hopes to present some of these best practices with respect to unbundling at its annual convention in November.

A big part of the unbundling equation revolves around service delivery. Specifically, which components of service are customers willing to pay for and which should be bundled with the delivery of the devices? The focus of this essay is not to discuss why or even how to unbundle. My purpose is to examine which components of the service experience are valued by the customer and how we can add more value to them, so that the market is willing to pay for these services. This process starts with a deep dive into the wants and needs of the marketplace. Examining the opinions of the market will serve us well as we fine-tune the unbundling process.

As the management guru Peter Drucker said, “the purpose of any business is to create a customer.” In an elective medical/helping profession like audiology and hearing instrument dispensing where we draw from a relatively narrow segment of the population, the creation of a customer can be extremely challenging. Thus it is imperative that we listen to the “voice-of-customer” before we make any significant decision about our businesses. Sadly, aside from the Kochkin MarkeTrak reports there is little voice-of-customer information available. I did manage to stumble across one published report that shed valuable insight on what our customers think with respect to follow-up service.

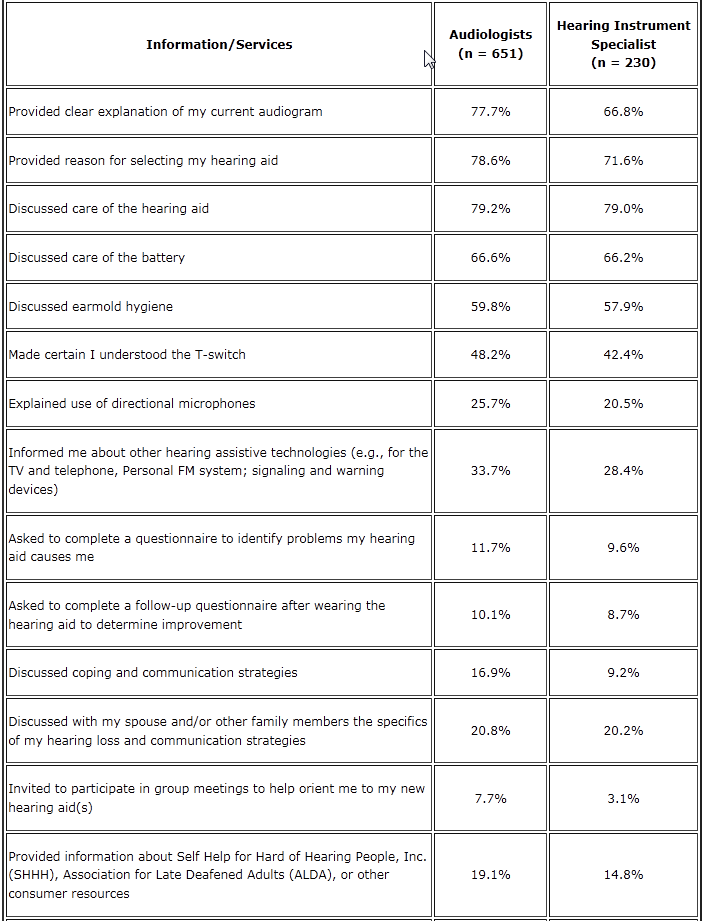

Stika and Ross (2011) surveyed 942 hearing aid users drawn primary from individuals associated with the Hearing Loss Association of America (known when the survey was conducted as Self Help for Hard of Hearing People). Their primary objective was to analyze the differences between services delivered by an audiologist and those provided by a hearing instrument specialist from the customer’s point of view. Their analysis of the survey results, in case you are interested, was that individuals who saw an audiologist, on average, reported a higher level of satisfaction than respondents who were provided services from a hearing instrument specialist. You can read the article to see how big the service gap between the professions was reported.

The most actionable part of their article, however, was not that finding. Rather, it was their assessment of itemized services delivered by both groups of professions. Respondents were asked to recall which particular services they received from either their audiologist or hearing instrument specialist. Table 1 shows a breakdown of the percentage of survey respondents who received specific services. Not surprisingly, services that directly impact the use of the hearing aids themselves are provided more frequently by both groups of professionals.

Note that a much higher percentage of services that are inextricably bound to the hearing aid were reported to have been delivered by both groups of professionals. This provides some clear evidence direct from customers that, indeed, as my colleague and friend Barry Freeman suggests, the device is the center of our universe.

One could argue that most of the services listed in Table 1 were actually conducted by the professional, but the respondents simply did not remember it. After all, the authors did ask a group of elderly people to recall what happened at a prior appointment, which may have occurred several weeks ago. Granted that could be true, but it still doesn’t explain the much higher percentage of services delivered for device-centric activities. If you ascribe to the poor memory recall argument, also keep in mind that patients are less likely to recall something that was not emotionally compelling and memorable. That is yet another reason to make your routine interactions with patients energetic and even entertaining when you can.

Table 1. Percentage of Respondents Indicating Services Provided by Either an Audiologist or Hearing Instrument Specialist. Source: Stika and Ross, 2011.

Audiologists Should Implement These 5 Things before Unbundling Services

Originally posted at HHTM On July 16, 2014. Reprinted with permission.

What Do These Findings Mean to the Profession and Your Business?

Before considering an unbundling strategy practitioners would be wise to implement the following:

- Beef up the service experience. An easy place to start would be to provide every patient with general coping and communication strategies. These educational materials can be delivered in written and spoken form. Books, handouts, DVDs are all available. For the professional, the important point is to inspire your patients to care enough to actually watch the DVD or read the book. Inspiring patients to care is probably something you didn’t learn in school, but in an age when customers have unprecedented choices your ability to use your personality and interpersonal communication skills to engage patients emotionally makes a huge difference.

- Provide more than simple informational counseling. Consider using Performance-Perceptual Counseling. Saunders and Forsline (2012) evaluated two different types of counseling sessions and their impact on outcomes for a group of experienced hearing aids users. One group was provided information counseling, which was a general explanation of test results, encouragement to discuss experiences relative to communication with hearing aids and recommendation about how to more effectively use their devices. The second group was provided performance-perceptual counseling (PPC). PPC requires the audiologist to measure speech recognition in noise ability objectively and then subjectively. Patients who overestimate their ability to understand speech in the presence of noise are counseled differently from those who underestimate their ability to understand speech in the presence of noise. The authors also used several standardized self-reports of outcome as well as a semi-structured interview to measure the results of these two different types of counseling. Responses to the semi-structured interview questions showed both types of counseling had a beneficial effect on patient’s outlook toward communication and benefit from amplification. Their findings suggest that periodic follow-up appointments that provide information on communication repair strategies and dialogue on how to cope with hearing loss and hearing aid use serve to enhance the benefit and quality of life that result from amplification – even for patients with hearing instruments older than five years. You could even create your own colorful handout that customizes coping strategies{{1}}[[1]]Handout example:Comm_Strategies_Checklist_MAY30v2 [[1]]depending on the outcome of the Performance-Perceptual Discrepancy.

- Inspire more patients to participate in support group meetings in which coping strategies and emotional support for the patient and significant other are discussed in an organized way. A good example of this is Louise Hickson’s Active Communication Enhancement (ACE) program.

- Customize the follow-up service. Here is one example involving auditory training: Auditory training is best described as a series of regimented exercises designed to take advantage of the neuroplasticity of the brain. Saunders (2012) evaluated the effectiveness of Listening and Communication Enhancement Exercises (LACE), which is one commercially available type of auditory training. In a three-site, randomized control trial with 263 veterans comparing LACE to informational counseling and a placebo (non-focused interaction with the clinician), she found all four groups experienced small, but significant improvements in handicap reduction and hearing aid benefit. These result indicate that auditory training did not outperform other types of follow-up services. However, Saunders (2012) found that a small number of individuals did significantly benefit from LACE auditory training. This research suggests there are opportunities to customize auditory training and counseling for individuals. We need ways to help us identify which follow-up tool is best for the individual earlier in the intervention.

- Demand more voice-of-customer analysis from academia and industry. Simply stated, audiologists and hearing instrument specialists could benefit from studies that tell us what hearing-impaired patients and their families want or need with respect to service. We are starting to see more such studies, but we need more well-designed studies that carefully examine the expectations and needs of our existing and potential customers. To quote Peter Drucker again, “Business has only two functions — marketing and innovation.” Our marketing efforts must include more “voice-of-customer” data and our innovations cannot be restricted to technology. We must innovate around service, especially if the trend is for independent practices to differentiate around it.

Service innovation need not be confined to the fitting and follow-up appointments, as these are still largely centered on the dispensing of a device. In the third and final post of this series, we will examine service innovation at the initial point of patient contact with your practice and look at ways services can be truly decoupled from the sale of a device.